The Weekly Orbit is a (sometimes) weekly column collecting and refining my more casual anime- and manga-related thoughts from the previous week. Mostly, these are taken from my tumblr blog, and assume at least some familiarity with the works covered. Be wary of spoilers!

Hello there, anime fans. I’m struggling with a bit of the ol’ burnout on my end, but I think I’ve managed to put together a pretty nice column for you this week regardless. Hopefully you agree. 🙂

Anime – Seasonal

Call of The Night – Season 2, Episode 10

I don’t know when, exactly, during this episode it became clear to me that Anko might be trying to commit suicide-by-vampire, but it hit me like a brick when that turned out to actually, genuinely be the case.

I really think this show’s second season has proven to be just incredible in a way I don’t think I would’ve predicted at the end of the first, even accounting for the fact that I liked the first season a lot. The intense emotion on display all throughout this episode, Nazuna and Anko’s horribly painful divorced yuri, Ko getting caught in the right place and saving Anko’s life, and then in the wrong place at the end of the episode when her gun goes off as she’s trying to kill herself….man, I don’t really know what to say here beyond this is a really exceptional series. I think my favorite of the many little touches across this episode was Nazuna ripping up playground equipment when she starts really trying to stop Anko. Playground equipment, you see, as a symbol of innocence, destroyed because neither of them can ever go back to it. Honestly, just brutal, what an episode.

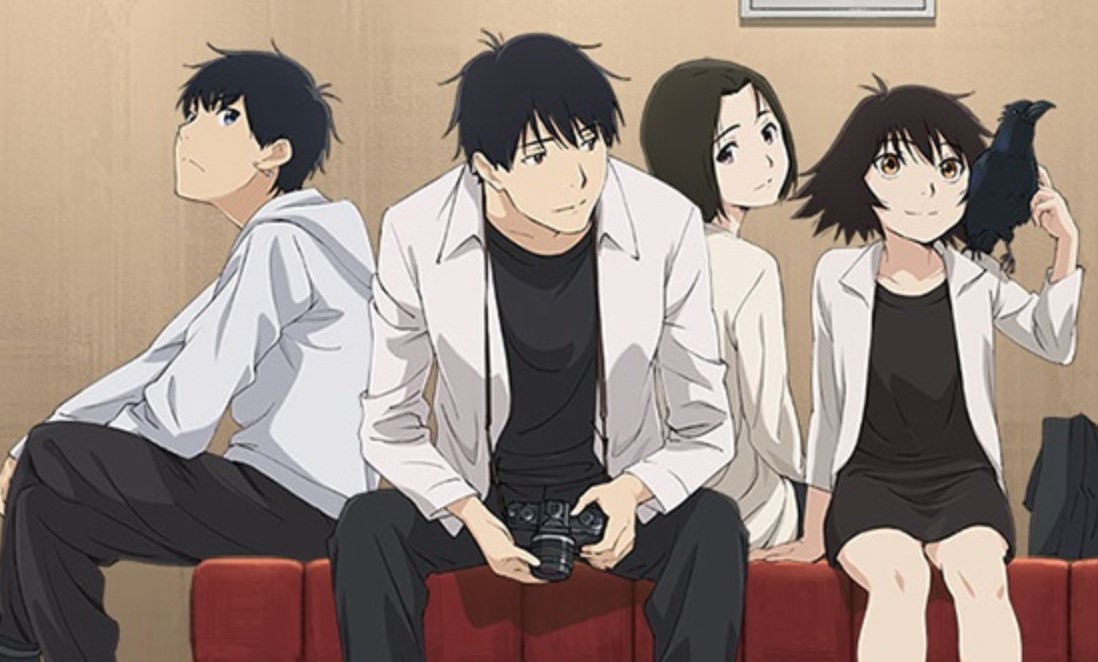

Dandadan – Season 2, Episode 10

Last week we had a fight, and then comedy. This week, we have comedy, and then a fight. Simple!

This is the episode where we’re first introduced to Sakata Kinta [Fujiwara Daichi], although I don’t think we get his name here. His introduction as a weird nerd—an even weirder nerd than Okarun, in fact, by a mile—who makes inappropriate dirty jokes because he thinks it helps him seem cool is a bit of a slow start in terms of actual characterization, but I have to admit it is genuinely pretty funny. The first half of the episode also has a Tom & Jerry sort of quality to it where Momo and Okarun are looking for each other at school and keep missing each other, eventually literally running into each other and prompting Kinta’s surprise that Okarun is “popular with the ladies.” (Presented as Kinta getting the wrong idea in-fiction, but he’s not really wrong, given that both Momo and Aira are interested in him.)

Naturally Kinta gets dragged into a battle with the supernatural when the “gold ball ghost” that was mentioned last week turns out to actually be an invisible monster using high technology to shield itself from sight. Our heroes seem to defeat it (even Kinta makes a small contribution), but it rises again, growing gigantic and promising a full-on kaiju battle next week. I have to give it up not just to all of this show’s usual strengths here but also the music, the kaiju theme sounds like a drum n bass remix of the Godzilla motif. Lovely stuff.

My Dress-Up Darling- Season 2, Episodes 9 & 10

For all my complaining about the slight hit Dress-Up Darling took with that diet episode a couple weeks back, it returns here with two of its best episodes maybe ever. This is what I get for complaining and, hey, full credit, I couldn’t be happier. Two main things happen over the course of this arc. Let’s talk about the less consequential and funnier one first.

First of all, this arc involves Marin’s friend group prepping to do a group cosplay of some characters from a horror visual novel called Coffin. Unlike the series’ usual formula, the dramatic push and pull here doesn’t come from Gojo having to make an outfit. Marin’s buying a simple off-the-shelf number this time, but Gojo is still going to be involved in setting up the cosplay, so he wants to learn more about this visual novel regardless. He visits Marin plays the game at her place, and of all of the various style emulations that Dress-Up Darling has engaged with over the course of its run, this is some of the most impressive. We get scenes from the VN rendered in tastefully faux-retro, dithered pixel art. As Gojo plays, it goes from being a fairly straightforward slice of life thing to being an absolutely brutal psychological horror story about killer nuns and familial abuse. (And from what we see of it, Coffin really is a pull-no-punches kind of game. It’s easily the sort of thing you could imagine grabbing off of itch.io. And, perhaps, end up regretting that you didn’t read the trigger warnings, depending on how squeamish you are.)

Gojo being Gojo, he doesn’t see this coming at all, and to paraphrase his own words, gets a bit hyperempathetic about it. Worse, he doesn’t actually have Marin with him for the majority of his playthrough to bounce off of. He’s also hopped up on energy drinks, because, surprise, the trains back home are out of service and his whole hanging out with Marin has turned into an impromptu sleepover.

Why is Marin asleep? Well, when she sees our boy buying the energy drinks, they happen to be right next to an aisle of what I’ll politely call supplements and gets the wrong idea. So she spends most of the night anxious that Gojo is trying to make a move on her, even as she also kind of looks forward to it, her head spinning with ideas about how they’re going to do all of the “important stuff”—handholding, kissing, and yes, sex—in one night. It’s a little rare for an anime to have noticeably good body language animation, but the way the show focuses on her eyes, dialed into tight, beady little pupils, and toes, twiddling and scrunching up into little balls of anxiety, is really something. It also noticeably never feels even a little bit salacious, since in this context, Dress-Up Darling—never afraid to be horny when it wants to be, and I must stress that that’s fine in its own right—wants you to appreciate Marin as a person with her own thoughts and feelings, not as something to ogle.

After eating some instant ramen, Marin calms down, sharing an adorable story about how her and her dad used to share the very same kind of ramen while watching movies together late at night. In fact, she gets so comfortable while talking about this that she actually falls asleep, and Gojo puts her to bed, leading to his own odyssey with the visual novel above. (It feels like a pointed contrast that Marin, a well-adjusted and happy girl over all, shares a warm and positive anecdote about her father. The protagonist of Coffin, by contrast, is horribly abused by hers.)

With the clarity of morning, Marin beats herself up a little bit about getting so anxious—and so excited—over a simple misunderstanding. She wonders if Gojo actually likes her in that way at all, and in doing so she imagines him rejecting her, which shakes her so badly that she actually starts crying. Her anxieties are dispelled though upon visiting Gojo at his house a day or two later. Gojo, ever-considerate, sometimes overly so, actually tries to turn her away at first. Not because he doesn’t actually want her there, but because he made fried fish for dinner, and isn’t sure if she should be having that, given her stated dieting goals. Marin is moved enough that she just decides today is a cheat day, and she enjoys dinner with her crush.

Still, she can’t actually work up the nerve to outright ask him out. She tries to, but eventually scales the request back to just asking to come back tomorrow. (He says yes, of course.) On a late-night train, the warmth from their time spent together crystallizes into determination, and she promises herself that after the Coffin group photoshoot, she’s going to ask him out, come what may.

I admit I’ve never been super concerned about the overarching “plot” of Dress-Up Darling. It’s always pretty clear in this kind of thing that the leads are going to get together eventually, it’s just a question of if it’ll take the whole series or only part of it. Still, it’s really exciting to see actual progress being made on that front. Even if it’s a feint in the immediate short-term, the character development here speaks volumes. Marin herself, pondering her and Gojo’s relationship, points out that teasing him used to be easy, but now that she’s actually worried he might reject her, she can’t bring herself to do it anymore.

There are complicating factors; one of the other people involved in the group cosplay—Akira, who were introduced to just a few episodes ago, a mysterious and somewhat reserved girl who primarily cosplays her own characters (awesome, it must be said)—doesn’t like Marin for some unstated reason. This, along with Sajuna’s return to the series and her own reluctant involvement with the Coffin shoot, promises to throw at least one, maybe several, wrenches into this whole business. Still, I’m really looking forward to how this arc resolves, there are a lot of parts in motion here, and I am so fascinated to see how they intersect.

Necronomico & The Cosmic Horror Show – Episode 10

You can say a lot about Necronomico, much of which is not exactly flattering, but damn if it isn’t memorable.

There are two main plot threads in this episode; Kanna contending with Ghatanothoa’s game for her—a supernatural raising sim based on her own life—and Kei being played like a fiddle by Cthugua.

In the case of the latter, I don’t think it’s even explained to us what Gua’s “game” actually is, but she spends her entire half of the episode alternately insulting Kei and calling her a pretty doll, while at the same time making her drink sake until she’s so drunk she can’t see straight. Eventually, this culminates in the two of them kissing and burning to death together in Gua’s palace. I’ll be honest, I have no idea where exactly this came from, but as far as tragic (and commendably strange) yuri goes, it’s pretty good.

Kanna’s half of the episode is a bit more thematically meaty, in that Ghatanothoa’s game is directly based on her own, very sad life, and to discover its true ending (and thus win it) she eventually figures out that she has to make no decisions at all.

“You can’t really change the past” is, as Kanna herself angrily points out, exactly the kind of obnoxious and overdone theme that someone like Ghatanothoa would gravitate towards putting in a game like this, with its presentation of that theme equally so. Despite his bloviating about how all of human art and culture is meaningless, Ghatanothoa is essentially portrayed as a parasocial fanboy, in fact, complete with calling Kanna his “oshi”, and his amateurish-at-best command of visual novel writing reflects this. I commend the show for not taking the easy way out of saying that Kanna’s suffering is what gives her life meaning, but it is a little hard to swallow that this leads to another mutual kill. I get why it has to be set up that way; so Miko and Cthulu can hinge the fate of the world on their final confrontation, but it doesn’t really square with what we’re shown here.

And, well, all of this has to put up with the fact that this episode has some of the worst boarding in a show that, even at its best, has not exactly looked fantastic. Still, the end is in sight by now, so I am interested to see if they stick the landing. My personal theory is that this show doesn’t actually have the stones to commit to a bittersweet ending and we’re going to get everyone revived at the last minute somehow. The still-hanging plot thread of Kanna being “favored by Azatoth” would provide the perfect off ramp.

Oh, and no Eita this episode is notable, if only because it means he will inevitably be back next week.

Turkey! Time to Strike – Episode 9

Fundamentally, right, the whole “bowling” motif in this show, it’s a gimmick, right? Or it at least seems like it should be one. You could write a very similar story to this without that aspect of it at all, and people have. But, more than just a way to stand out from the pack, the way the series uses the sport to actually emphasize the communal nature of play as an idea is like….forgive me for not finding a better way to say this, it’s just not something you really expect from a random seasonal anime. Which is absurd, right? Because every anime was a random seasonal anime at some point. There’s not actually a distinction. But it nonetheless manages to surprise me every time one of these shows actually turns out to be this good.

So, you have this episode. A thwarted—thank god—double suicide and winding, beautiful conversation about what it means to mean something to someone, how people put themselves on the line for those they truly care about.

And of course, there’s how the episode ends, with a thundercloud rolling in, the promise of home on the horizon. Will our heroines actually leave? After this episode, I think it’s very up in the air. It’s clear that the two halves of our cast care for each other a lot, but there are still three episodes to go, so there’s plenty of time for interesting developments.

Oh, and can I say? Starting the episode by immediately catching the viewer off-foot with the altered OP sequence? Brilliant.

Other

Ano Hi no Kanojotachi: day09 Miu Takigawa

It has been five years since early lockdown-era idol anime 22/7 tried, and failed, to reinvent its genre.

22/7 the idol group, though, have ticked on. They still exist, and have persisted through a variety of lineup changes, a notably rocky history that has resulted in multiple changes in direction for their sound and, admittedly, given them more of a fanbase than you might assume if you don’t follow idol stuff very closely. Takigawa Miu, the group’s center, was one of two remaining original members. As you can glean from the existence of this short, she has now left. “Graduated,” as it is somewhat-euphemistically referred to among idol fans.

This short is ostensibly a sendoff. It’s not actually even narratively related to the 22/7 TV series (it has more in common with, and is presented as, an episode of the 2018 slice of life shorts that were created early in the lifespan of the project), but it marks the end of something, so it’s still significant, as both a point to reflect on what 22/7 was and is and what its existence can tell us in general about the circles of art and media it is a part of.

Miu’s vocal performances—both voice acting and singing—were provided by Saijou Nagomi. (She technically reprises the role here, but doesn’t speak, contributing only a few soft sobs at one point. These could easily have been provided by a fill-in or pulled from archive audio, but I’m choosing to assume some amount of professionalism here.) Five years is a long time in the entertainment industry, and watching this short, and its quiet melancholy, I cannot help but wonder how she must’ve felt to have it playing behind her during her farewell concert, as that is the context for which it was originally produced.

It is worth noting that Miu is Ms. Saijou’s only voice acting credit of any note, and if she’s ever released any other music, I was not able to find it by doing a cursory search. Still, a glance at her Twitter page indicates she was keeping it professional up until her very last day in the group. There is lots of talk over there of cherishing every moment she spent with her fans and so on. As of the time of this writing, the most recent post is a handful of images from the farewell concert. Some digging reveals she intends to largely make the transition to behind-the-camera work as a photographer.

The short itself largely portrays Miu in transit; first coming home on a bus, and then, after quietly crying to herself in bed, going somewhere that looks an awful lot like a college or new school of some other sort, in what is either a dream sequence or a flash-forward. It’s definitely playing into these sorts of thoughts; where is she going from here? Is she happy? Does she have regrets? On some level, all of that is as much an emotional manipulation as any of the more obvious work done by any number of more traditional idol anime—before or since—that 22/7 sought to join the ranks of and perhaps surpass. (And we have to give credit to Wonder Egg Priority director Wakabayashi Shin that this is imbued with such emotion in the first place. The short has no dialogue, as mentioned.) Still, it’s overall a surprisingly moving piece of work, and one that feels ever so slightly out of step with where the medium’s sensibilities currently are, with its vibrant and shiny lighting that feels so tied to the visual aesthetics of the last decade as opposed to this one. I said it’s a long time in the entertainment industry, but honestly, five years is a long time for anyone. The short is a potent, if brief, reminder of this.

The last scene of the short shows us Miu, on a bus, looking back at the camera. We don’t know where she’s going, but she is going. It’s hard not to feel happy for her. And as strange as it may be to say, that shot, as it fades out for the final time, is probably the most 22/7 has ever affected me. Perhaps tellingly, it did it without “subverting”, “reinventing”, or “deconstructing” anything.

And that’ll be all for this particular week. As always, I ask that if you enjoyed what you’ve read here (or just enjoy my site in general), you consider a donation to my Ko-Fi page, it helps immensely, and helps keep the site up and running.

For this week’s Bonus Image, please enjoy the title screen of Coffin, perfectly evocative of the evolving title screens of RPGMaker games and indie visual novels of both the past and present.

Like what you’re reading? Consider following Magic Planet Anime to get notified when new articles go live. If you’d like to talk to other Magic Planet Anime readers, consider joining my Discord server! Also consider following me on Anilist, BlueSky, or Tumblr and supporting me on Ko-Fi. If you want to read more of my work, consider heading over to the Directory to browse by category.

All views expressed on Magic Planet Anime are solely my own opinions and conclusions and should not be taken to reflect the opinions of any other persons, groups, or organizations. All text is manually typed and edited, and no machine learning or other automatic tools are used in the creation of Magic Planet Anime articles, with the exception of a basic spellchecker. However, some articles may have additional tags placed by WordPress. All text, excepting direct quotations, is owned by Magic Planet Anime. Do not duplicate without permission. All images are owned by their original copyright holders.