It’s always a weird thing to have to write about why you didn’t like something. I’m a big believer in the idea that positive criticism is both more important and more difficult than negative. Yet, the format of the list means that we’re starting with several anime that I consider the very worst of the year (and indeed these first two entries are….not what I’d call favorites, we’ll put it that way). It admittedly makes me a bit nervous, because negativity is not my preferred mode of criticism.

Yet, at the same time. I think that even bad anime can expand one’s frame of reference and provide interesting insights into the medium in general. My hope is that this first part of the list does the same for you.

#20: The Day I Became A God

As I write this, it’s been about half an hour since I finished The Day I Became A God. This is the second-to-last anime I needed to finish for this list (the entire thing, all four parts), and I really, genuinely did not think I’d be adding something this far down this late in the game. I have to rewrite the opening sentence of my next entry, which in its current draft now-falsely claims that it is the only anime on this list to make me genuinely angry. That’s no longer true! Frankly, The Day I Became A God‘s final three episodes are so far and away the worst television period that I have watched this year that it’s made me see every subsequent entry on this list in a better light.

To talk about the latest from Jun Maeda and his colleagues at Key, we need to talk about how it starts. Because understanding how The Day I Became A God transforms from a pretty solid slice of life comedy with a supernatural edge into one of the most galling, maudlin, hacky attempts at a make-you-cri-everytiem love story that I have ever seen requires understanding how we got here. Or rather how we didn’t.

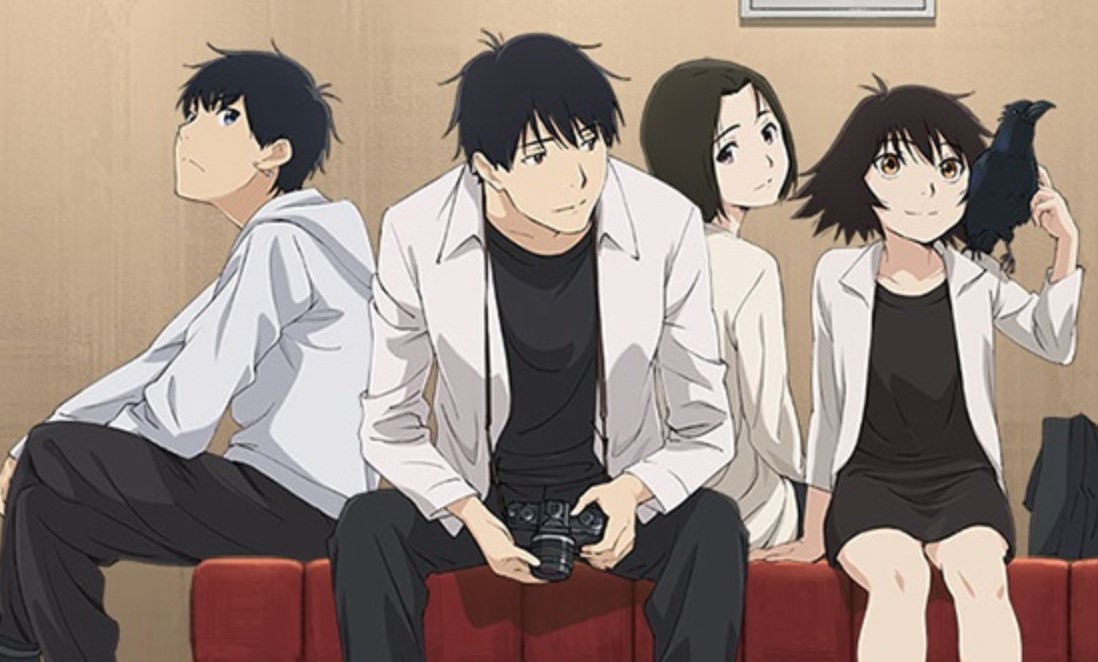

The Day I Became A God concerns Hina, alias Odin. It feels like a lifetime ago that the character was introduced to us as a blithe esper with the power to know anything. The first two thirds of the series chiefly concern her adventures with Youta, the inoffensively bland everydude protagonist. They do fun things like cheat at mahjong and help a ramen restaurant turn its fortunes around. It’s hardly groundbreaking, but it’s good fun, and if that were what we were discussing here this series would be assured a comfortable spot somewhere in this list’s mid-section with all the other solid genre anime.

Jun Maeda’s signature as a writer–so I’m told, anyway–is to build up the relationship between the characters and you, the audience, with this kind of every day life fun. Then, near the series’ end, some sort of Sword of Damocles will drop, the drama will hit, and tears will flow. Indeed, I knew this going in to The Day I Became A God, and am familiar with the device from the only other work of his I’ve seen–Angel Beats!, an anime I actually like quite a lot. The show even appears to foreshadow this; the anime’s other core premise is that Hina can sense that the world will end in thirty days.

So, fair play, right? Why am I mad?

If only this show dealt with something as interesting as apocalypse. Instead, for its final third, through a series of plot contortions so mind-bogglingly ridiculous that I will not recount them here, Hina is abducted by a shadowy government organization and has the source of her powers, a machine in her brain, removed. It’s revealed to us that, actually, Hina was severely physically and mentally disabled this entire time. (Because of a fictional Anime Illness, of course. God forbid you give your disabled characters any actual condition.) It was only the sci-fi magic of the machine that was allowing her to do what she did with Youta and friends, in addition to being the source of her omniscience. Are you crying yet?

The Day I Became A God‘s final three episodes are not just bad, they’re slimy. I actively felt repulsed by 11 and 12 especially. I absolutely loathe calling things “cringey”, but I physically winced at the screen during scenes in which (through another series of plot contortions) Youta, woefully-unqualified, tries to return her to his home where she lived for most of the series by posing as a physical therapist. These episodes go through great pains to portray Hina as pitiable because she is largely nonverbal and physically handicapped. In a particularly insidious twist, the show frames Youta’s generally ridiculous actions as being somehow, secretly, what Hina “wants”. It is a framing that cannot help but feel gross, ableist, and exploitative.

The finale, in which her actual doctor lets her return with Youta and the gang watches a student film they shot during the series’ first half (pointedly, when Hina was still verbal and able-bodied), feels like having this nonsense rubbed in your face. One has to go back a solid ten years, to 2010’s Occult Academy, to find a series that suffers a drop in writing quality this precipitous in its final 90 minutes. Even then, I think this example is genuinely worse.

I am left to wonder; who is this for? I make no secret of the fact that I am a massive sap, but the tearful reunions in the final episode of The Day I Became A God did absolutely nothing for me. My eyes remained dry, my fingers drummed in irritation on my desk, and I could only feel relief that the show was over.

Maeda has said he intended to create “the saddest anime ever” with this series. The only thing he succeeded at was making one that is profoundly frustrating, disappointing, objectionable, and, frankly, insulting to its audience. I considered cutting this series some slack with its placement here; after all, those first two thirds do still exist. But I actually think that they make the finale even worse. By the end of The Day I Became A God, all of my goodwill and any endearment I felt toward any of its characters had been sandblasted away by one of the most colossally inept TV anime endings in recent memory. All involved can–and should–do better.

#19: Sing “Yesterday” For Me

The operative word for Sing “Yesterday” For Me is “unfortunate”. This is another one with a promising start that slowly careens into an unsatisfying finish. It’s not quite a worst-case scenario for adapting old material into new anime, but it’s close.

But let’s start with the positives, because despite what that sentiment might imply, I can easily imagine why people who aren’t me might like the series. “Yesterday”‘s earthy, grounded visual style and accompanying soundtrack give it an aesthetic sense that is a genuine treat. Plus, it helps make the show’s slow narrative go down more easily than it might otherwise. It also has its moments of self-awareness, such as in an episode about a photographer whose obsession with one of the female leads, high school girl Haru, parallels protagonist Uozumi’s own.

So what’s wrong with it? Nothing and everything.

“Yesterday”‘s entire premise rubs me the wrong way. What is markedly worse is that through no one’s fault but my own, it took me the entire length of the series to realize this. (You can find material on this very blog where I praise the series, in fact.) Saying I have something of an irrational grudge against this anime wouldn’t be entirely wrong.

“Yesterday” is ostensibly the story of the aforementioned Rikuo Uozumi, a young adult working a dead-end job, and two potential love interests; Haru Nonaka and a former classmate who is now a teacher, Shinako Morinome. To its credit, both Haru and Shinako feel like fully-fledged characters. While their relationship (or lack thereof) with Uozumi does dominate their arcs, it dominates the entire plot, so that only makes sense. The real issue is pretty simple; Uozumi is a college graduate, and while Shinako is his age, Haru is a narratively-convenient eighteen. After much hemming and hawwing over the course of the series, Uozumi and Haru kiss in the final episode. Roll credits.

Fundamentally, even if you don’t find age gaps creepy, the way Uozumi treats Haru until the closing fifteen or so minutes of the final episode gives every indication that he’s going to end up with Shinako, despite what is framed as a somewhat childish fixation on Haru. But if this were merely a case of bait-and-switch or of one’s preferred Best Girl not winning, it’d be a minor gripe at most. The back half of the show’s final episode throws everything the narrative has been building toward wildly out of whack. The series’ real, actual problem then, is that like so many romance anime, it ends where it should begin.

The idea of a college grad who is finally starting to pursue his photography dreams after waking up from the torpor of the layabout life while having to juggle a relationship with someone years younger than him is wildly interesting. It’s also arguably super weird, but that’s an angle a story can work with. Why does Sing “Yesterday” For Me take so long to get to what is by far the most interesting development in its story, and then just end?

There are no answers, at least none for me. I have spoken to others who enjoyed the series and a common view I find is that the series is about building up to lifechanging moments, to sudden pivot points from which there is no return. More power to the folks who can find it in them to read the series this way, but I cannot. Thinking back, I find myself craving a more properly developed drama. I can only consider “Yesterday” a disappointment.

#18: The God of High School

I’m genuinely not trying to be meanspirited with these first few entries, because I fully acknowledge that making any anime requires an immense amount of talent from many people all working in concert. It’s a process I could never be involved with and I do genuinely respect anyone in the industry grind, no matter what the end result is.

So with all that said; what on earth do you say about something like The God of High School? The God of High School is not really what I’d call a bad anime, and despite its abundance of hyper-compressed shonen cliche I’d say it’s still fun enough on a moment to moment basis. But it really is the sort of series that one struggles to describe not because it’s particularly inscrutable but because anything you could say about it also applies to many other, better-known (and just better) anime. For instance; I could tell you that it’s a tournament arc-heavy series where the protagonist lacks much characterization beyond a desire to fight and is loosely based on Sun Wukong, but you might then assume I’m talking about Dragon Ball Z. Other aspects of the series similarly feel so heavily indebted to its predecessors that saying anything positive (or even neutral) about it that couldn’t easily be mistaken as praise for Dragon Ball or Bleach or Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure or almost any other shonen series is extraordinarily difficult.

The issue is just that The God of High School feels very much like what it is, which is an animated adaption of a webcomic written by a shonen junkie. Consequently, while it’s fun in the places where it truly lets itself cut loose (such as the more out-there fight scenes), it feels dreadfully anonymous much of the rest of the time, and even when it is firing on all cylinders the breakneck pace of the adaption means it’s generally for only a couple minutes at a time. There are worse things to be than a decent way to burn six hours, but as it further recedes into the rearview I’ve come to realize I cannot imagine I’ll ever watch even a second of it again. And more than any other show on this list, I can even less imagine what a diehard fan of The God of High School would look like. If this is more indicative of the quality of what’s to be produced under the Crunchyroll Originals banner than a certain other Webtoon adaption that shows up elsewhere on this list, that is really not a great sign for future CR Original material. I would like to think it’s an outlier.

#17: 22/7

Maybe it’s unfair to call 22/7 disappointing. Yet, looking back on it a few months removed from its airing that’s the adjective that first springs to mind. 22/7 seemed poised to offer something interrogative and worthy of thought; early episodes gave the impression of building up to some kind of grand reveal, positioning the series as something of a would-be Madoka for the idol girl group anime genre. Whether through deliberate misdirection or just too-high expectations on some part of its audience, it never got there. Instead, as weeks stretched into months, it simply gradually ran out of steam until limping across the finish line at the end of its season.

Even setting that aside though, 22/7‘s command of character writing is pretty limited. Every character arc is hamstrung by the show’s bizarre editing, which likes to cut backward and forward, interweaving flashbacks with scenes of the present day. It seems likely that this is supposed to draw a deliberate contrast; how our idols got from where they were to where they are. Instead, it generally makes episodes thematically and tonally incoherent. Even the best of them (such as Jun’s focus episode) are often hamstrung by dicey writing. At its worst, as in episodes revolving around more minor and frankly less-interesting characters like Reika, it hauls in hoary sexist ideas of what an idol should be that feel stuck in the ’80s. It’s impossible to prove that these somehow stem from the involvement of industry oldguardsman Yasushi Akimoto, but his presence in the background of the series’ production does not incline me to charitable interpretations of the 22/7‘s flaws.

The show does have its positives, of course. It’s generally nicely-animated and sometimes well-directed, especially in the case of the aforementioned Jun episode, and it has solid character interactions even if the arcs are not particularly strong. But I think if 22/7 the series survives in the collective cultural conscience at all, it won’t be through the lens of the show itself. 22/7 is also an actual idol group, and their music ranges from solid to, at its best, fantastic. The melodramatic cloud of black smoke they turned in for the show’s opening theme–a cheery number about how life is hard and no one understands each other called “Muzui” or “It’s Difficult”–remains one of my favorite pop songs of 2020, and I found myself returning to it many times over the course of this difficult year. Far more time than I ever spent appreciating the series it’s a theme to. 22/7 the group have a bright future. 22/7 the anime is best left in the past.

#16: Burn The Witch

Burn The Witch is a weird one, for one several reasons. It’s not a TV series, for one thing (the only such entry on this list), and it’s in the odd position of being the adaption of just the first few chapters of its source material. Something that would likely have never happened were the writer of said source material not Tite Kubo. The man most famous for the polarizing–but undeniably very successful–Bleach. Burn The Witch has a lot of things going for it. It’s animated by Studio Colorido, and being made as a three-episode special means that it’s never less than great to look at, and the fights in particular here are superb. The worldbuilding is goofy but in a fun sort of way; you know that things are off to a good start when we get a made-up statistic about dragon-related deaths in London right off the top. Our two protagonists, Noel and Ninny, are also quite fun to follow, each in their own way. Even the show’s magic system is a good time, more anime could stand to experiment with goofy horn-guns as their weapons of choice.

So all that said, why isn’t this higher up (or, well, lower down, one supposes) on the list? Well, not to repeat myself, but Burn The Witch has a man-shaped millstone hanging around its neck.

It’s really hard to overstate how much of a problem male lead Balgo Parks is, as a character. He’s sexist, he’s obnoxious and he’s everywhere. He completely kills the fun any time he’s on-screen, and he’s on-screen all the time. It’s a terrible, terrible problem for an otherwise solid OVA to have, because every second he’s there he’s cutting into the actually enjoyable parts of it, and ultimately, he ruins it. Time will tell if this applies to any further adaptions of Burn The Witch we get (and it’d be surprising if we didn’t get at least a season or two of a TV series), but I certainly hope it doesn’t.

#15: Gleipnir

Grisly, grody, sometimes flat-out exploitative seinen adaption that’s a mess from top to bottom. I feel like if I were a more “respectable” commentator on the medium I’d hate this show. But I’m not, so I don’t. I wouldn’t say I like it either, exactly, but it’s definitely the entry in this part of the list I have the most nice things to say about.

Gleipnir‘s been a part of my life for an unusually long time compared to the rest of the entries on this list. I first read the manga (which I markedly did not care for) back in 2017. When I heard of an anime adaption premiering this year I was curious to see if it’d be improved at all by the change in medium, and, admittedly, I was hoping that if it didn’t, it’d at least be a fun thing to riff on with friends.

To a point, that is exactly what I got. Gleipnir‘s idiosyncrasies too often fall on the bad side of good taste for me to really call it great. There are too many offputting shots of the show’s female lead in her underwear covered in fluid, weird problematic or just straight-up uncomfortable elements (a centipede demon from the show’s 2/3rds mark springs to mind as an example) for that to be the case. And its male lead is the kind of shonen-protagonist-but-edgier that just doesn’t leave you with a ton to work with most of the time.

But nonetheless, there’s just something about this series. Maybe it’s the surprisingly good action direction and atmosphere, which is certainly a credit to both director Kazuhiro Yoneda and his team at PINE JAM in general. The man has episode direction credits on the grandfather of 2010s trainwreck anime; Code Geass R2. While I can’t prove that the experience somehow uniquely equipped him to deal with Gleipnir‘s ridiculously up and down source material, but it wouldn’t surprise me. Over the course of its single cour Gleipnir manages to, in spots, eke out some surprisingly affecting character writing, has a downright haunting final few episodes, and, as mentioned, some great fight scenes. An example in the final episode might still be one of my favorites of the year as it unites both the show’s literal reality and its thematic core of relying on others to compensate for your weaknesses and confronting your demons in a way that it otherwise struggles to articulate. Gleipnir‘s central issue is its tendency to get in its own way, but that’s hardly a rare problem for the medium.

I don’t know if a second season would fix (or even mitigate) that problem, but Gleipnir is the only anime in this part of the list where if one were released I’d be interested in watching it. That must count for something, surely.

And thus we finish the “unpleasant but necessary” part of the list. Still, even among these unlucky few there is not a single one among them I actually regret watching, not even The Day I Became A God. I have said many times that part of what draws me to anime as a medium is its infinite capacity for surprise. That surprise is not always pleasant! But you take the bad with the good.

Speaking of the good, I will see you in Part 2 when it goes live. Happy Holidays!

If you like my work, consider following me here on WordPress or on Twitter, supporting me on Ko-Fi, or checking out my other anime-related work on Anilist or for The Geek Girl Authority.

All views expressed on Magic Planet Anime are solely my own opinions and conclusions and should not be taken to reflect the opinions of any other persons, groups, or organizations. All text is owned by Magic Planet Anime. Do not duplicate without permission. All images are owned by their original copyright holders.